This is an extended transcription of my CreativeMornings talk. The theme was “Make,” and instead of speaking about my own work, I decided to talk about my dad, his work, and how he turned me into the maker I am today.

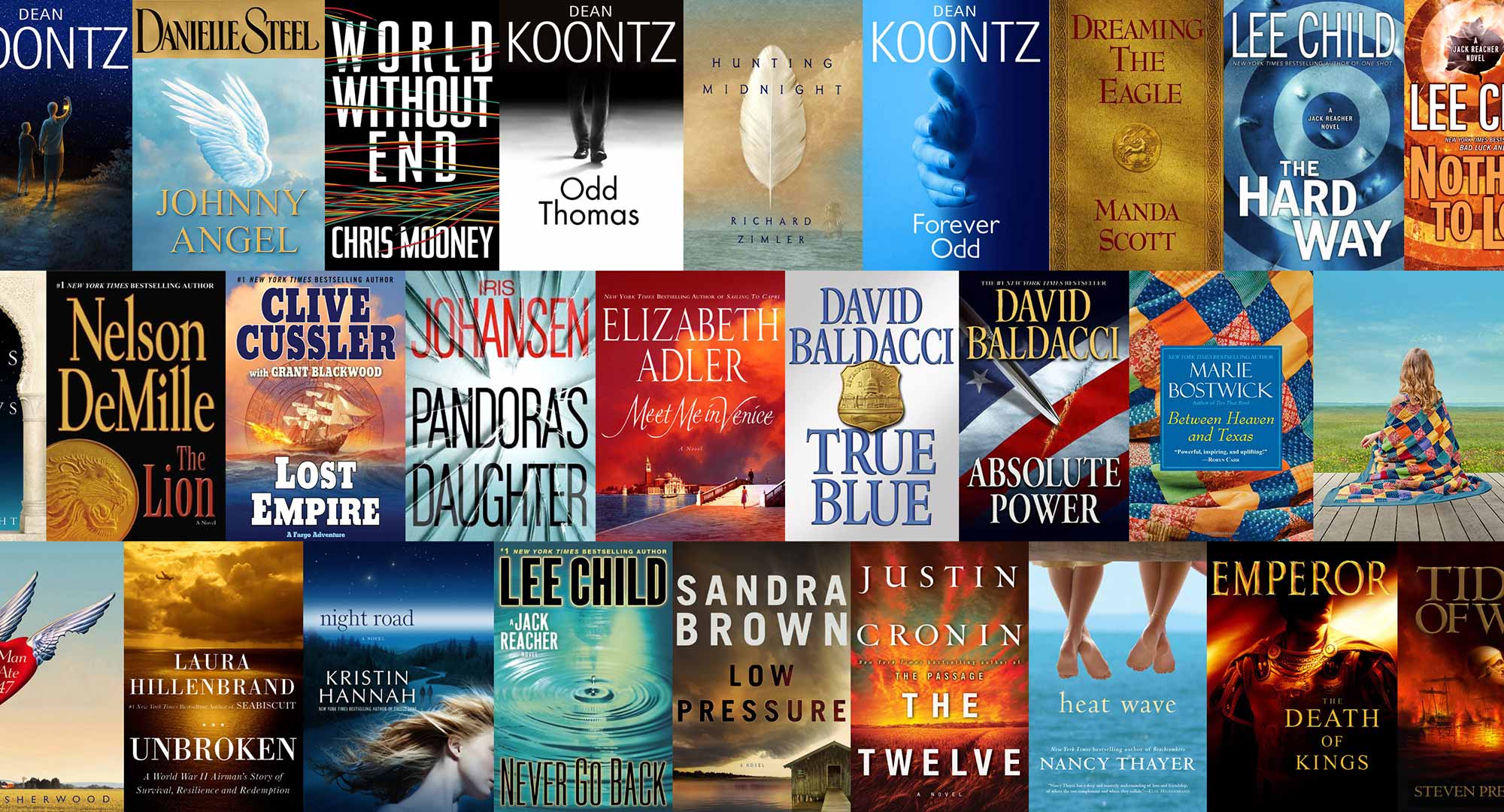

My dad is a freelance book cover illustrator. He started right out of college and has been pushing out covers ever since—about 37 years now. If you’ve ever been in a book store, you’ve seen one of his covers. If you’ve walked past a cardboard box on the street with a stack of books in it, you’ve seen one of his covers.

For the first 20 years, he painted each and every cover. He would take a few reference photos with his polaroid land camera and spend the following month painting with acrylics on a gessoed masonite board. Upon finishing, he would slip the cover in a Fedex box and ship it to his publisher in New York, hoping it would arrive in one piece. Now, my dad uses Photoshop. He can start a cover on a Friday and email it to his publisher on Monday.

Since my dad works from home, my siblings and I grew up watching him illustrate these covers. He greeted us in the morning from his studio and wished us goodnight from his studio. My dad burns the midnight oil better than anyone I know, which explains why working a 14-hour day sometimes feels normal to me. Some nights, we would work alongside each other in his studio, watching any given Philly game, with the audio from the local radio broadcast.

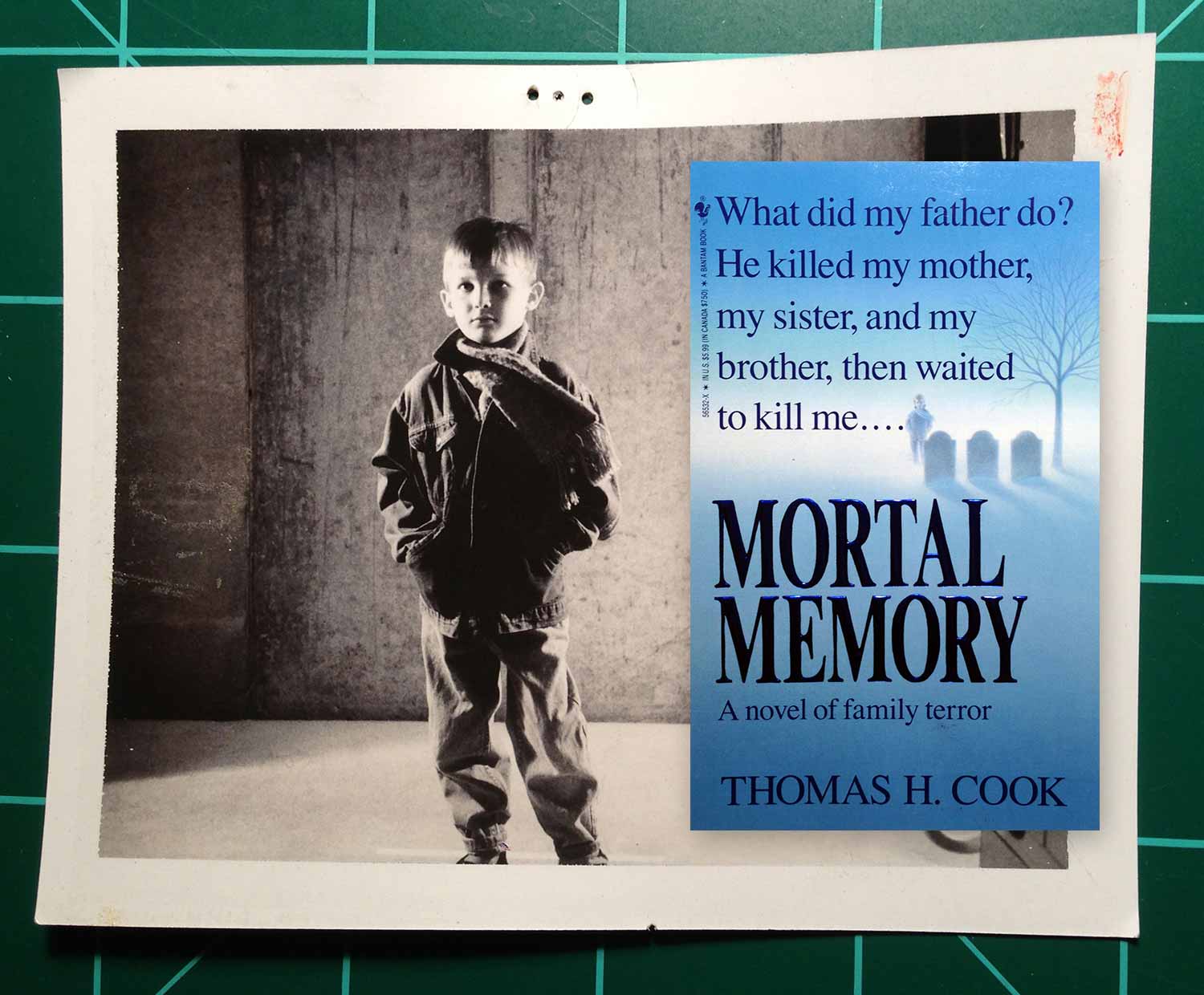

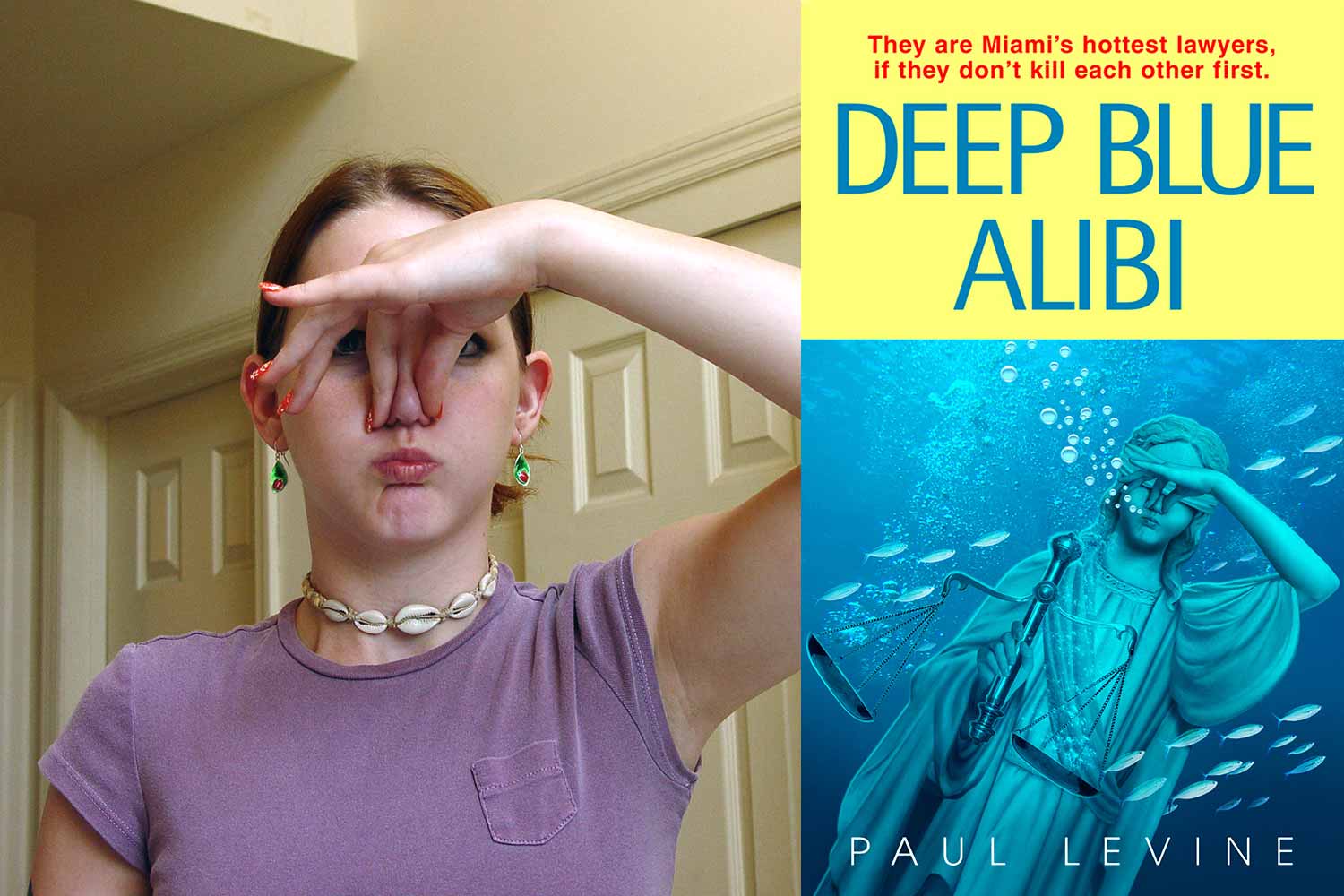

Because my parents live in the small town of Macungie, PA, my dad would ask us to pose for him rather than hiring models. At the time, there was nothing special about this—it was just part of our childhood. I would spend a few minutes looking like a boy without a family and he would pay me $20, which I could use towards my next video game. To a kid, this was a steal.

Posing for my dad was rarely planned—he would just call us over from his studio and ask us to spare a few minutes. The shoot often involved my mom holding a piece of foamcore as a makeshift reflector or picking out the correct attire for us. We would goof around, treating this like our own version of dress-up.

After holding still for a few shots, trying to make each other laugh while not laughing ourselves, we would go back to whatever we were doing. Then, several months later, we would find ourselves on another cover. This felt like magic. My dad doesn’t need green screens or professional lighting—he can make a cover out of anything.

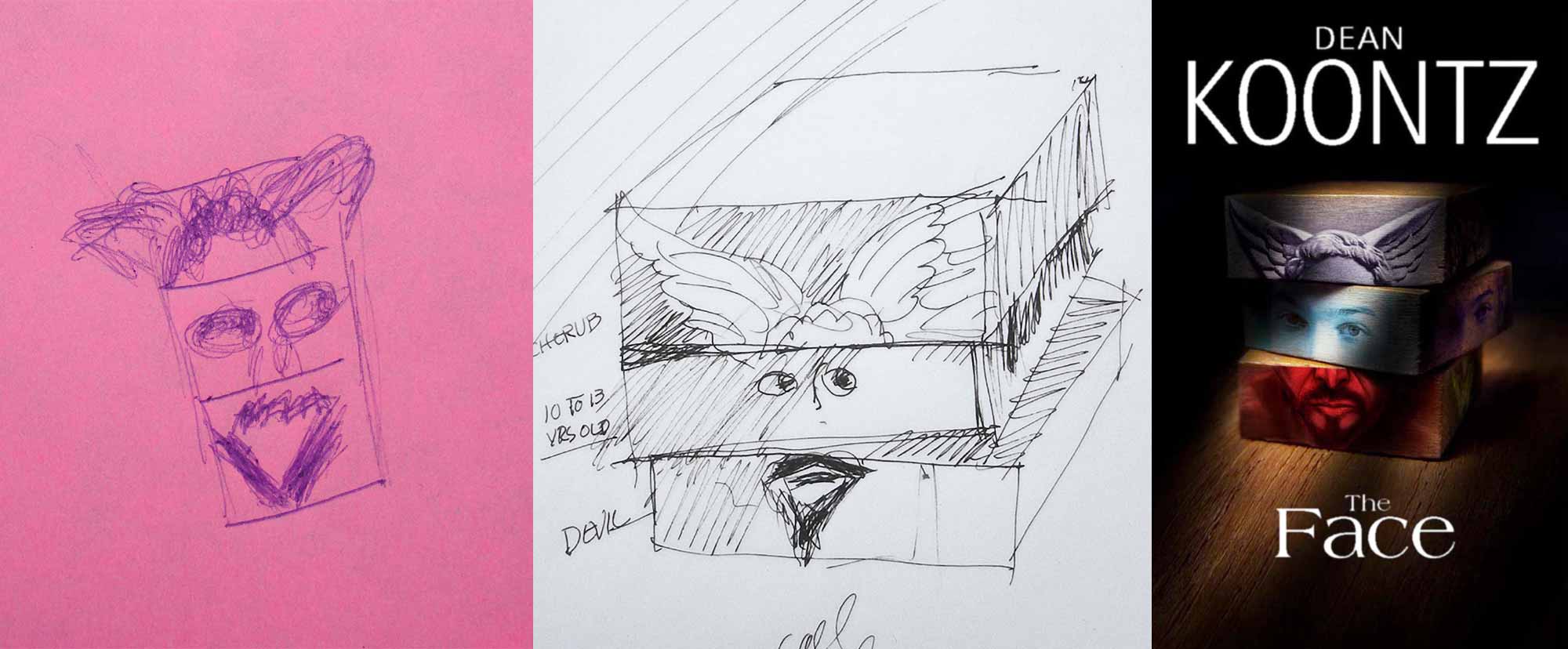

To start a cover, one of my dad’s publishers would send him a sketch. The sketch was often more of a scribble than anything descriptive, so they would follow up the sketch with a call. The art director would chime in and provide a sketch of their own. This would typically be more elaborate, but still difficult for most to interpret. My dad had no problem, though. He would take these sketches and produce a cover with the exact image his publishers had in mind.

Because of this, his publishers would consistently return to him when they needed the job done right. This had a major impact on my own work ethic and the kind of relationships I try to build with others. If you establish yourself as someone who can always finish the job with a level of quality beyond expectations, you will never have trouble finding work.

Though my dad is at the top of his game with book covers, his true passion lies with model airplanes. When he wished us goodnight from his studio, he usually had an airplane in front of him rather than a cover.

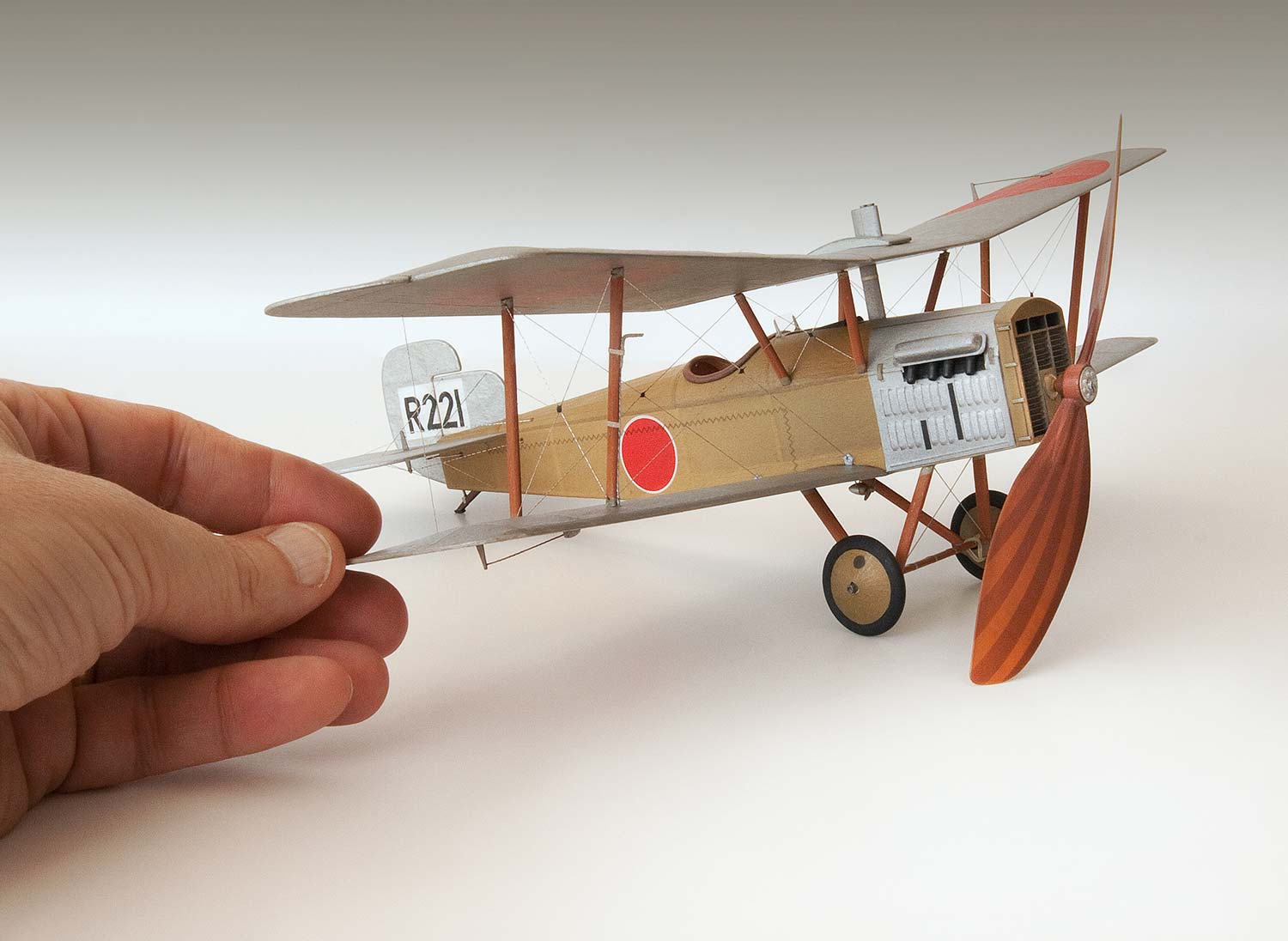

He started building airplanes at the age of eight, having learned from his dad. Back then, video games and computers didn’t exist (*gasp*), so models were a common hobby for the average kid. Hobby shops are rare these days, but if you can find one, there’s a good chance it will have a section for model airplanes. But, my dad doesn’t just build his airplanes from kits. He actually constructs them from scratch, and each one is an exact replica of an existing airplane from a previous era, mainly WWI and WWII.

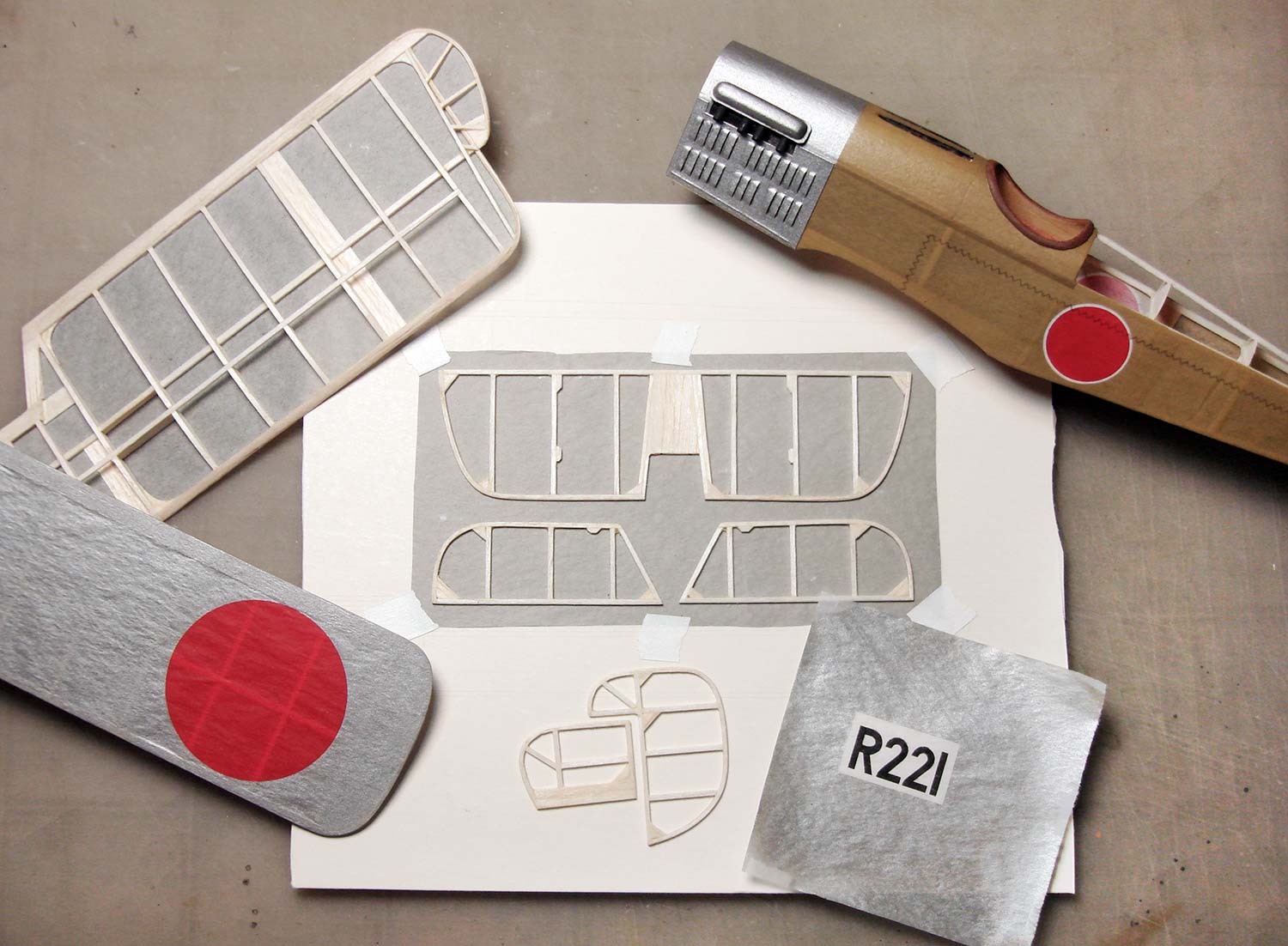

A single airplane will take anywhere from two months to a year to complete. Each one is constructed from several sheets of balsa wood that are cut down to size and glued in place. The airplane is then wrapped in tissue paper and decorated with all the details of its original design. As a kid, I witnessed the daily progress of every plane—each one built as separate parts, then pieced together at the end. Now, I see progress in months, when I’m able to visit home. I’ll catch him either starting a new plane or putting the finishing touches on one I’ve seen only once or twice before. Nevertheless, he’s always excited to show me his latest creation.

Building model airplanes requires enough work on its own to be considered a full-time job, let alone a hobby, but my dad isn’t the type to just shelf a piece of work and call it a day. Every airplane he builds can also fly as well as it looks. In his eyes, what’s a plane that can’t fly? He takes this very seriously, too, to the extent of mowing only a portion of his backyard, so the rest could remain a soft “landing strip” for testing and minor tweaking. He calls it “Hallman’s Meadow”.

As you might expect by now, these airplanes aren’t RC-powered. Believe it or not, they fly on rubber band power. Inside each airplane is a greased rubber band running from a hook in the back to the propeller in the front. The length of the rubber band depends on the size of the airplane, with some reaching as long as several feet.

Winding one of these airplanes by hand would be very tiring, not to mention time-consuming, considering a single flight requires several hundred winds. Instead, my dad uses a makeshift winder. This MacGyver-esque device can wind ten times faster than using your hand. It also comes equipped with a calculator that keeps track of the number of winds, using a magnet that is literally taped to the crank. Surprising no one, you can’t buy these—he knows a guy who makes them.

My dad also competes as a member of the Flying Aces Club. He drives to either Geneseo or Wawayanda in upstate New York and flies against dozens of other “pilots”—each of whom has been building and flying airplanes for decades. They spend a few days competing, but also discussing their craft, process, and experiences from the past year’s build. Having been to several competitions as a kid, I can tell you that each one of these fliers wants nothing more than to share what they know and celebrate each other’s flights.

At the age of 59, my dad is considered the young gun among the other fliers, with most of them old enough to be his dad, but as a 5-time grand champion, he carries a strong reputation.

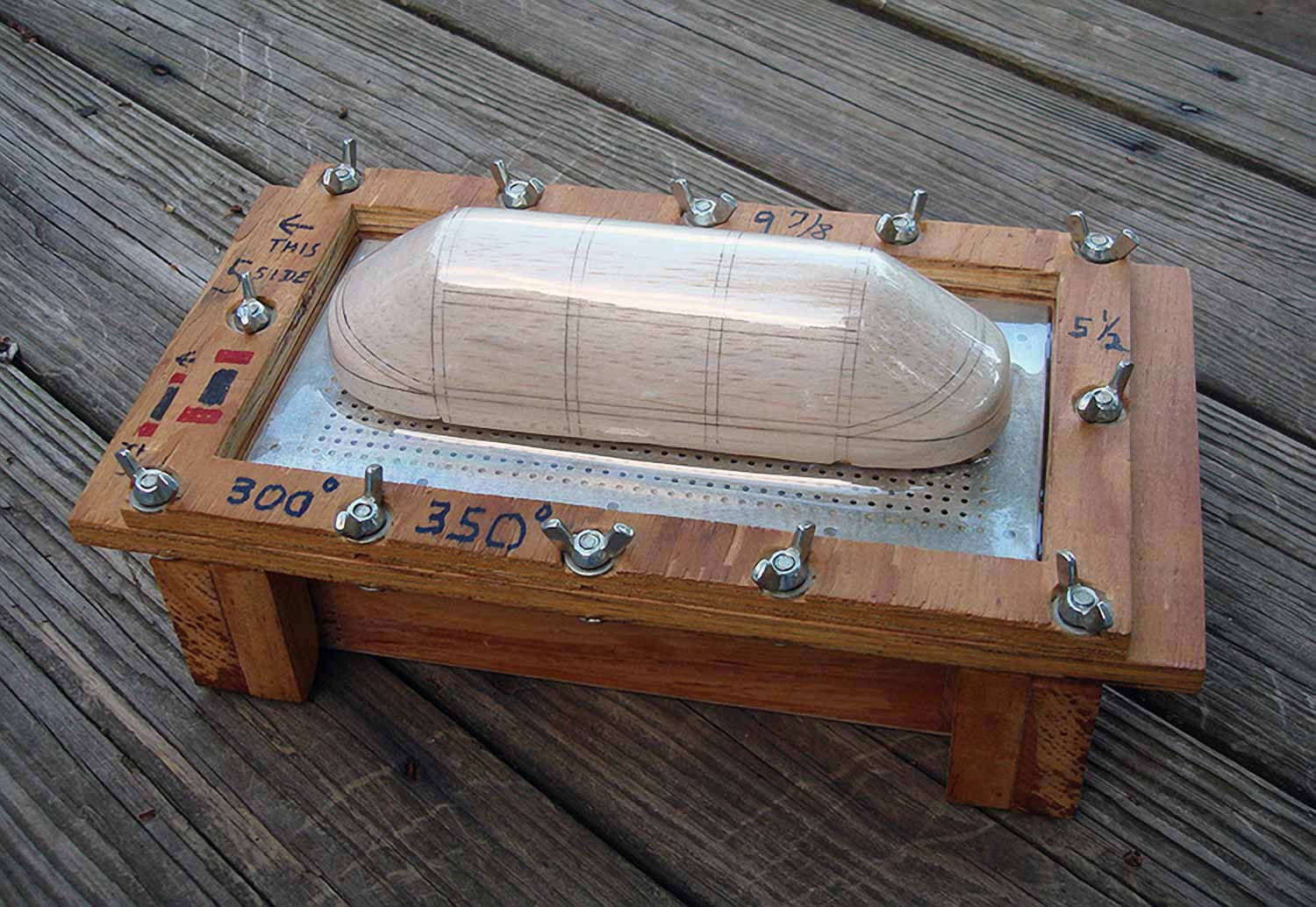

Along with constructing the actual airplanes, my dad also builds tools to help him make specific parts of each plane. One of these tools, he calls a “canopy vacuformer”, is a contraption that forms the canopy of an airplane from a single sheet of plastic.

My dad places the top-half of the tool in his oven with the plastic securely held in place. The plastic is heated at a temperature between 300-350 degrees, until malleable. Then, he removes the plastic from the oven and places it on top of the balsa mold of the canopy. With the family vacuum, he suctions the plastic down to perfectly fit over the mold, forming the canopy of the airplane.

As a kid, growing up watching this process, I didn’t think twice about it—this was just how you build the canopy for a rubber band-powered model airplane. How else would you do it? Now, I truly appreciate the creativity and resourcefulness on my dad’s part to even think of a process like this, utlizing household appliances.

The attention to detail my dad puts into every airplane is incredible. His obsession with even the most minute details is one that I often see in myself. Every time he reveals his latest workboard of airplane parts to me, I soak in every consideration he shares and admire the precision of each piece. Everything is always perfect. In my own work, I want people to feel the way I do when I see his work.

While constructing an airplane, my dad takes the time to document the entire process, which is why I do the same with my own projects. I love seeing how each part comes together and how it contributes to the final product. Seeing this documentation as a kid, I learned its importance in telling the story of each airplane. I could witness the struggles, decisions and sacrifices that lead to the end result, making every airplane so much better.

My dad’s airplanes are more than just airplanes. Each one is a piece of art and an extension of my dad. Though these planes don’t really matter in the grand scheme of things, they mean the world to him. He taught me everything I know about craftsmanship and what it’s like to be truly passionate about our work. And, I’m passionate about my work because of my dad.